Fay Farm: Moos to Moors

The Path to Nobsque

Take a walk down Elm Road in Falmouth, Massachusetts, from Locust Street to the beach, as people have been doing for centuries. Imagine it unpaved, the land undeveloped, with virtually treeless expanses that allow unobstructed views of the ponds—Salt and Oyster—and Vineyard Sound. This was an Indian trail to Nobsque long before English settlers arrived.

|

| Unpaved cartway through Fay Farm was formerly an Indian path, now Elm Road (looking from 216 Elm up the hill to the southwest). (1916 Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Historical Museum Archives) |

Then as years pass, imagine small farms, live stock, laundry drying on a line. Dinner might have been fish just caught in Oyster Pond, with peas and corn from the garden, maybe a glass of rich Guernsey milk.

Elm, as it was eventually named, was designated a town “highway” in 1857—the first in Falmouth. It began at today’s Locust Street and came to a dead-end near what is now Nonquit Road. In 1925 it became a paved roadway, its path altered slightly as it crossed the railroad tracks (now, the Shining Sea Bikeway) and reached Surf Drive.

On your walk you will pass what is known today as 103 Elm Road. Early settler, and arguably the founder of Falmouth, Jonathan Hatch built his house into the hillside there c. 1659, soon after sailing into Salt Pond—then an open waterway to Vineyard Sound. The foundation of the house that exists there today—built in 1880 for dry goods merchant Bartlett Holmes—is believed to be that of the Hatch’s log cabin. “Hard by the rising ground,” Jonathan wrote, “I build my house.” It was possibly the first building in Falmouth.

Across the street at 122 Elm Road sits the 5-bay Colonial house that Moses Hatch built c. 1686. The son of Jonathan, Moses (1662-1747) was the first settler’s child born in Falmouth.

Moses’ property included a 40-acre farm. In his will, he referred to the land to the southeast of his house, running to Salt Pond and to the Beach, as “my English meadow.” It’s reported that he grew tender English hay there. For a period in the 20th century, Moors residents played golf there.

The houses at 216 and 228 Elm were built in the colonial style c. 1740 for brothers Daniel and David Butler who were farmers. It is generally agreed that David’s house at 216 is a bit ‘newer’. After it changed hands several times, Henry Fay bought the property in 1887 and the house became the farmhouse of Fay’s 120-acre dairy farm. In 1925 the house was lifted and turned around about 45 degrees to face the newly paved Elm Road and was set back about 45 feet to its present location. David’s house, along with 100 acres of farmland, was bought by Henry H. Fay in 1887.

|

| David Butler’s house, c. 1740, later known as The Cottage” , now 216 Elm Road. Salt Pond is seen behind the house. (1916 Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Historical Museum Archives) |

In 1889, Henry Fay offered use of the house at 216 Elm (David Butler’s house) then known as ‘The Cottage’ to the Emanuel Church of Boston as a vacation spot for the city’s working girls. The success of that philanthropic project led Fay to have the colonial revival “Recreation House” built next door at 202 Elm Road in 1902. Women and their children, mostly from Boston tenements, were given 10-day vacations that offered a slice of country life and wholesome food. The program continued for 25 years until Fay sold the farm. The hearth motto in the living room at 202 read:

‘This is the port of rest from troublous toil, the world’s sweet inn from pain and

wearisome turmoil”.

These three houses at 202, 216 and 228 are now part of our neighborhood and are, needless to say, the oldest houses in the Moors:

The Fays

By the 1880s, the land that lay between Salt and Oyster Ponds drew the interest of Henry H. Fay, son of Joseph Story Fay, a Boston merchant. The elder Fay had visited Woods Hole around 1850, liked it, and decided to buy a house where he and his family enjoyed many summers. His land acquisitions were substantial and the younger Fay followed his father’s example. In 1884, Henry Fay began to buy Falmouth land; three years later, he bought a hundred acres from George H. N. Davis and about twenty more from Ezekiel Ward. Together the parcels became known as the Fay Farm.

The Fay Farm

While not all of the land had been suitable for growing crops or grazing animals, the arable parts had been farmed by previous owners of the small farmsteads that made up Fay’s 120-some acres. The 1860 U.S. Census “Productions of Agriculture” schedules show that Beriah Tilton, gentleman farmer and master mariner, owned cows, mules, oxen, and swine. He raised Indian corn, peas, beans, Irish potatoes, and had ten tons of hay on hand. Neighboring farms generally had at least one horse, a few cows and pigs. They grew corn, peas, beans, barley, potatoes; some produced butter and cheese.

|

| Fay Farm Barn and Guernseys on site of today’s tennis courts. A smaller barn and 3 houses—now 228, 216 and 202 Elm |

Agriculture was not of primary concern to Fay, although his father had a great interest in forestry and horticulture. Henry’s farm was an investment in land—he leased parcels to others until it was time to sell. In the late 1800s, Tim Murphy farmed much of the land, known also as the “Honey Pot Farm” for its pond-side attraction to bees. Murphy was succeeded by leasee John Wray, an Irish immigrant who operated a successful dairy farm until 1924. His Guernsey cows, about 60 of them at one point, were sheltered in a 75- by 40-foot barn, which occupied the site of today’s tennis courts. The barn opened onto “the meadow”, a grazing area where today Moors residents organize softball games in the summer and happy dogs meet to frolic with their pals year round.

|

| Looking for golf or tennis balls? While these Guernseys weren't part of John Wray's herd, the idyllic scene suggests what you might have encountered in the Fay meadow (now the Moors field) a hundred years ago. (Photo: public domain) |

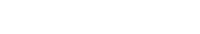

In 1921, Wray’s outbuildings included a smaller barn, a tool house and shed, two pipe wells, and an icehouse—the latter stocked with blocks of ice cut from the pond. This 1903 plan of the farm shows a pen, likely for the swine.

|

| Farmer John Wray’s hand-drawn plan of farm buildings (Courtesy of Woods Hole Historical Museum Archives). |

Wray, his wife, Josephine, and two daughters lived in the farmhouse, which had been built in 1740 for David Butler, and which had been occupied by many others in the intervening years. It was heated with wood stoves; it had no electricity; its water came from wells; its information by post, grapevine or The Enterprise. The publicly dedicated roadway—now Elm—ended at their house, but the ancient footpath continued to the beach.

|

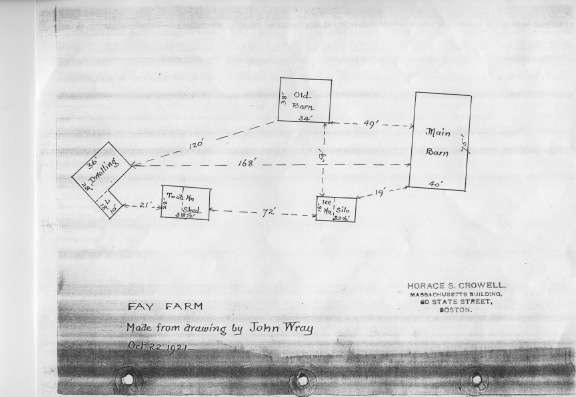

Milk for Sale

Wray touted his products in The Falmouth Enterprise, where one of his ads urged, “Try using a glass or two of the CELEBRATED FAY FARM MILK and see how much better you feel in a short time.” In another, he promoted "Baby Milk". (The Falmouth Enterprise, September 27, 1919, p. 5)

Open Spaces

As had long been the practice, brush was periodically burned, allowing for new tender new growth, colorful wildflowers and open vistas. But a new element was added to the landscape as the Old Colony Railroad opened service from Boston through Falmouth to Woods Hole in 1872. Tracks ran through farmland from the state highway (now Locust Street), past Salt Pond to the beach and on to Woods Hole. Trains hauled freight and they transported passengers who were seeking sea breezes and long summers away from city life. They now had easy access to a desirable destination.

End of the Farm

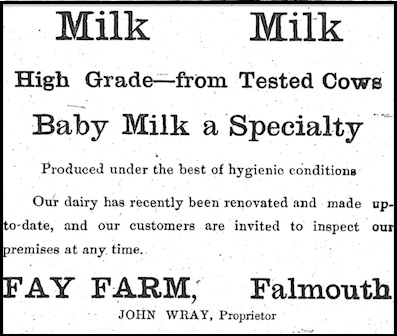

It was clear in the late 1800s that economic value favored residential development of land over farm use, particularly acreage near the beach and with water views for all—it would command top dollar. The dawn of the new century found Henry Fay ready to realize the opportunity offered by his investment in the farm. His land was ideal for a summer colony. In 1903, he commissioned John M. Curtis to draw a subdivision plan of lots, thus portending the eventual end of the Fay Farm. Laid out was a community of twenty-nine large lots meant to appeal to wealthy summer residents.

|

| 1903 Subdivision: "Plan of FARM BELONGING TO HENRY H. FAY Falmouth, Mass."of Fay Farm." Subdivision Plan by Jos. H. Curtis Landscape Gardener, January 1903. Legend at lower center reads, "Plan shows Proposed Development by Roads, Boat Landings, Reservations, and Division into Lots. Areas of Lots by scale measurement to center of roads. Total Area of Farm 125.78 Acres." Courtesy of Woods Hole Historical Museum Archives |

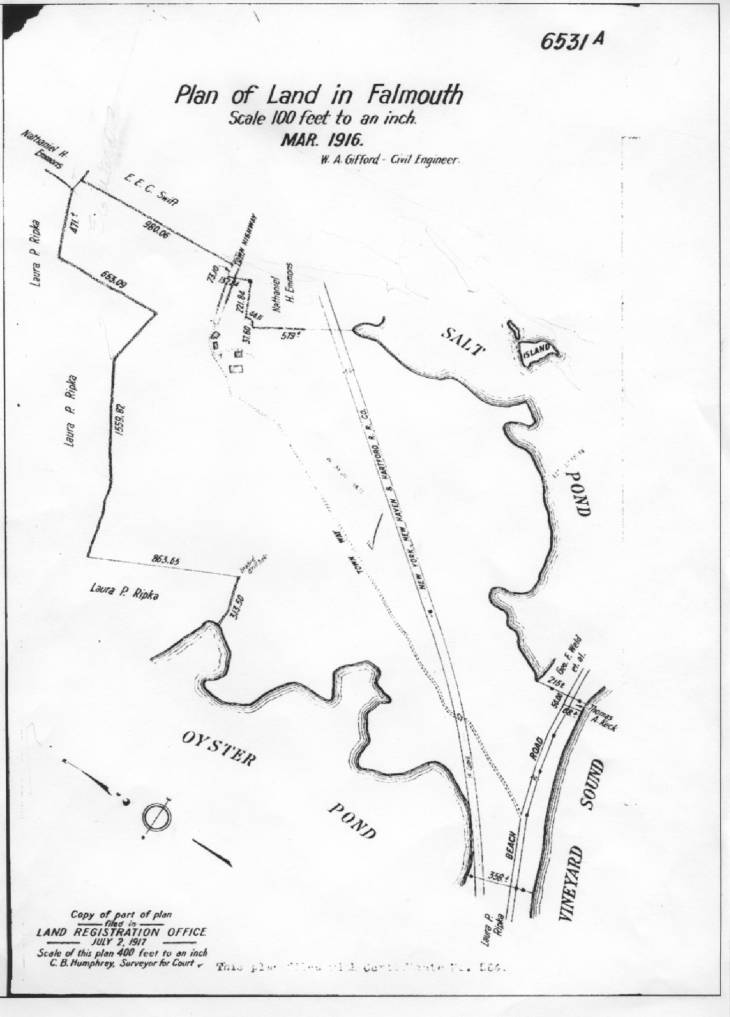

In 1916, apparently anticipating sale of the land, Fay had the title to the farm certified in Massachusetts Land Court. This established his uncontestable ownership of his land, which consisted of multiple parcels, often of irregular shape and approximate measure, that had passed back and forth through many hands—by deed or will—for more than two centuries. Purchasers from Fay could rest assured that no one could come forward with boundary disputes or claims of superior title.

|

| 1916 Plan (Land Court #6531A) showing boundaries of Henry H. Fay’s land that was sold in 1924 to the Falmouth Associates. |

A promotional brochure, “The Fay Estates: Seashore, Lake and Forest”, includes the farmland among various Fay properties offered for sale.

“THE FAY FARM,” otherwise known as the “HONEY POT FARM,” has an area of about one hundred and twenty acres, located on Elm Avenue and on the Beach Road. The larger part is remarkably fertile, level and under cultivation. The remainder consists of a series of knolls which attain a height of 86 feet, and from which are presented enchanting marine and landscape views. A set of farm buildings in good condition. Borders on Oyster and Salt Ponds and Vineyard Sound. Conveniently near to and west of Falmouth Village. Rare opportunity for a gentleman farmer of means, or for sub-division into much-desired cottage lots.

On March 4, 1920, Henry Fay died in Falmouth. It was another four-and-a-half years before the farm shut down and the cows began their trek up Elm Road. John Wray advertised in The Enterprise in November 1924 that he would be moving his dairy operations to The Coonamesset Farm. And he did, driving his herd down Main Street—passing the bank, hardware store, grocery market, theater, furniture store, and bakery. The Guernseys swished their tails and moseyed along the streets to Hatchville.

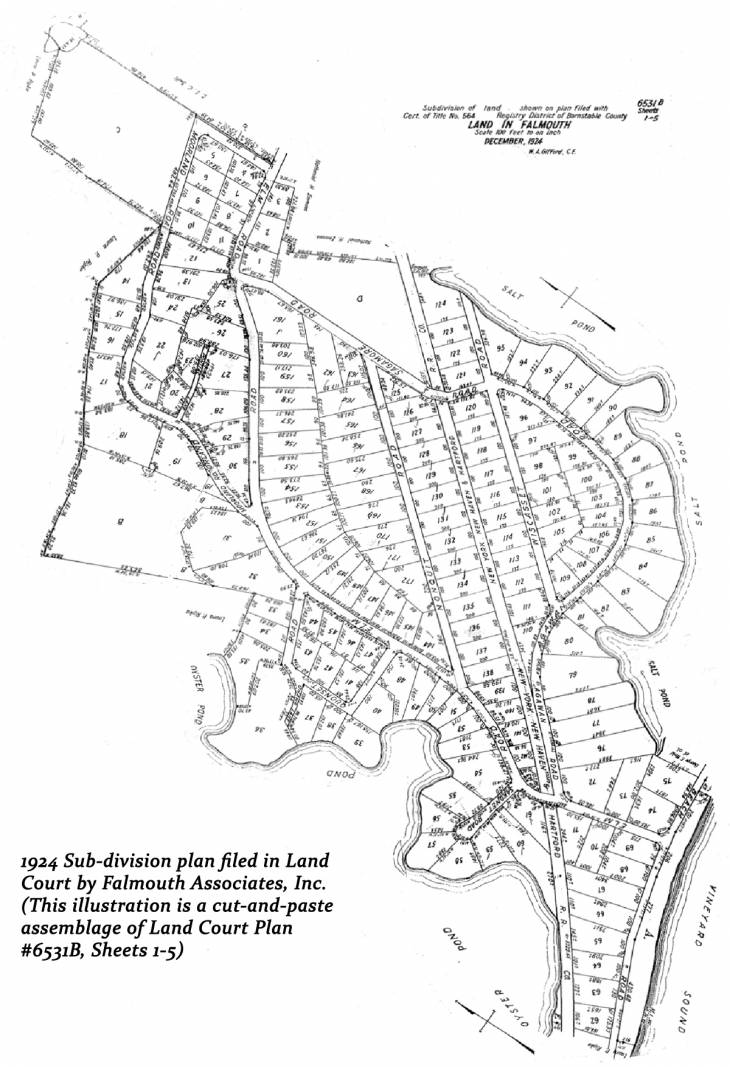

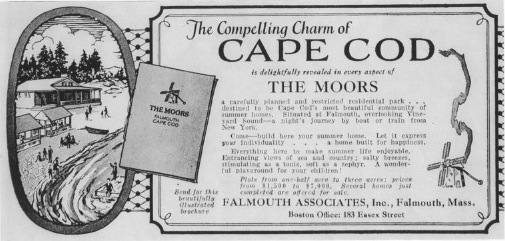

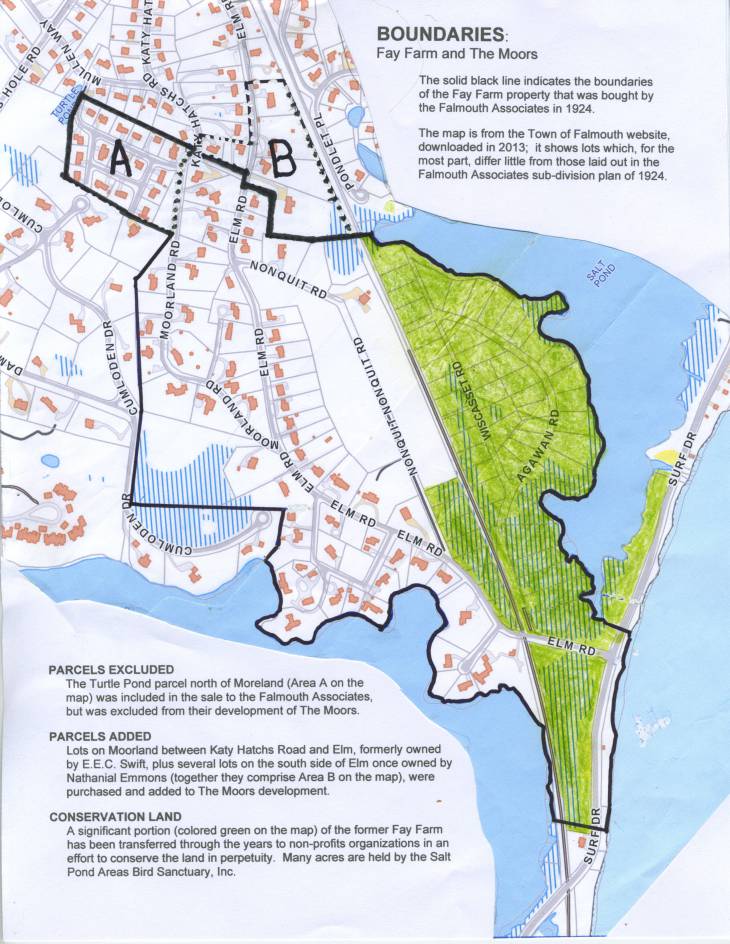

On October 30, 1924, just days before the Guernseys' departure, the Fay Farm with 120 acres and 1200 feet of water frontage, had been sold to the Falmouth Associates, a trio of Boston investors. Messrs. Robert T. Fowler, Thomas Lenci, and Harry W. Crooker called their development “The Moors” and envisioned a community of 172 lots, as shown below.

The Moors

In an illustrated 24-page booklet—“The Moors”—prospective buyers were assured in 1925 that this would be “a community, with every desirable city convenience, restricted to insure a high character of dwellings … with physical surroundings to suit every taste.”

It promised crisp sea air, good bathing, views, restful evenings, and sports. A 9-hole pony golf course with “several long, interesting drives” were offered “for the exclusive use of home owners at The Moors. A private beach pavilion with piazza, lounge and fireplace promised “adequate showers for men and women. Tennis courts and a croquet lawn were coming soon. (To see the entire booklet, click on "Moors Sales Brochure 1925" in the History menu to the left.)

Voices

Pages

- Home

- A brochure ALL ABOUT US

- Neighborhood Amenities

- CLUBHOUSE

- BEACH

- TENNIS COURTS

- BALL FIELD AND OPEN SPACE

- Tennis court reserved time

- Moors Governance

- About the Moors and Falmouth Assoc

- Moors Annual Business

- ANNUAL EVENT SUMMARIES

- Moors History

- Founding Fathers

- Fay Farm: Moos to Moors

- The Golf Course That Was

- Fay Farm sales brochure 1923-4

- 1933 newsletter

- 1945 Moors membership list

- 1961 Jackie Kennedy at the Moors

- Past Hurricanes

- Who planted the Elms?

- Photo Gallery

- Thanksgiving Day Plunges

- Tuscan Nights

- Community News

- Historical Photos

- Views of the Past

- Moors Sales Brochure 1925

- 66 Moorland Road circa 1933

- Moors players 1963

- Rental Opportunities

- RENTAL: 5 ONAWA LANE

- Local Services

- Summer 2024 Activity Calendar